A Voice from the Past: My Memories of My Grand Uncle KL Saigal

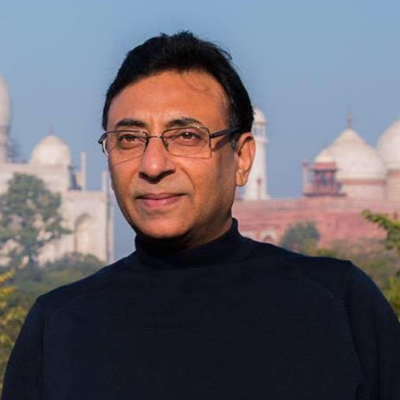

04 Apr, 2020 | Short Features by Sumant Batra

I grew up listening mainly to Mohammed Rafi and Talat Mahmood, my father’s favourites, although it was Kishore Kumar who resonated the most with me. But whenever I visited my maternal grandfather in Hisar (Haryana) during my vacations, I would hear him hum Kundan Lal Saigal’s Ek bangla bane nyara whenever he was in a good mood, and Jab dil hi toot gaya, hum jeeke kya karenge or Haye haye ye zalim zamana when in a somber mood.

Kundan Lal was second cousin to my maternal grandfather, S.P. Passi. I have a clear memory of my grandfather speaking at length about his superstar cousin and the days they spent together in Jalandhar. My great-grandfather was a headmaster in Kullu in Himachal Pradesh. His siblings had a family business in Jalandhar which included a radio shop. Kundan Lal’s father Amar Chand worked in the service of the Raja of Jammu and Kashmir as Tehsildar. Amar Chand’s sister was my great grandmother.

Kundan Lal was second cousin to my maternal grandfather, S.P. Passi.

Kundan Lal was born in Jammu on 11 April 1904, as one of five siblings. His mother, Kesar Devi, was a talented singer and encouraged her son to learn music. The two often sang bhajans in religious gatherings in their neighbourhood. Kundan Lal developed a passion for both music and acting even as a child. He actively participated in the local Ram Leela celebrations, playing the role of Sita. He also spent a great deal of time at the Dera of the Sufi saint Salamat Yusef, where he sang and honed his skills in thumri and ghazals, alongside other musicians and devotees. In his recently released book Kundan: Saigal’s Life and Music, Sharad Dutt relates an incident where the saint blessed Kundan and predicted to his mother that he would one day be a “great singer”.

Kundan Lal’s father, however, had an utter disregard for music; he thought it was “meant for the bhands and mirasis”, and wanted his son to focus on his education. But Kundan had no interest in his books and remained adamantly set on pursuing a career in singing. Soon, he dropped out of school and took up job of a railway timekeeper in Delhi.

Kundan Lal’s father, however, had an utter disregard for music; he thought it was “meant for the bhands and mirasis”, and wanted his son to focus on his education. But Kundan had no interest in his books and remained adamantly set on pursuing a career in singing. Soon, he dropped out of school and took up job of a railway timekeeper in Delhi.

His heart was in discovering the mysteries of music and singing. He used his travels to attend the baithaks of singers from renowned gharanas and folk singers, learning by observing them.

Amar Chand moved to Jalandhar after his retirement. Kundan quit his job and joined his family in Jalandhar where he took up employment as a typewriter salesman for the global typewriter brand, Remington, for a monthly salary of Rs. 80. The job provided him the opportunity to travel widely across the country. His travel took him to Lahore, Calcutta, Kanpur and other cities. His heart was in discovering the mysteries of music and singing. He used his travels to attend the baithaks of singers from renowned gharanas and folk singers, learning by observing them. He would practice in private and often repeat their songs in private gatherings. When in Simla (now Shimla), he honed his acting and singing skills at the National Amateur Dramatic Club, which staged plays at the Gaiety Theatre.

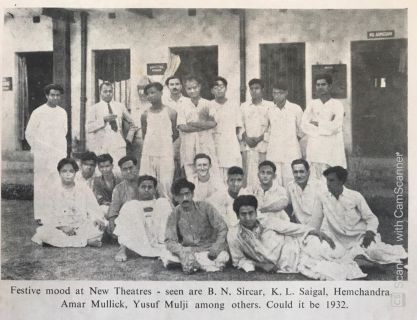

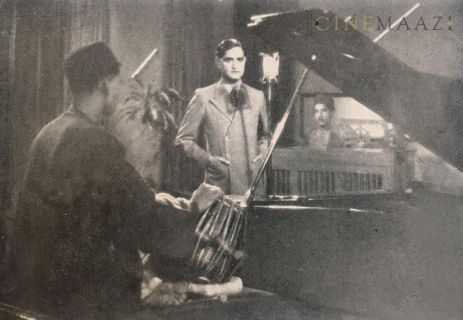

One of his friends, Mehrchand Jain prompted him to move to Calcutta, then an established hub of music and the other arts. In Calcutta, Kundan Lal took up a job as a hotel manager even as he started participating in local mehfils. In one such mehfil arranged by Ghazi Hassan, B.N. Sircar, the founder of New Theatres, and Nitin Bose heard him sing and were deeply impressed by his talent. The era of the talkies had begun, and playback singing was still in the offing. It was a time when actors and actresses voiced their own songs, and film companies were clamouring for singer actors. A gift for music was thus considered a prerequisite for a successful film career. B.N. Sircar promptly signed Kundan Lal for New Theatres on a contract of Rs. 200 per month. There he came in contact with stalwarts like Pankaj Mullick, Pahadi Sanyal, Aiyaaz Khan and K.C. Dey, who helped him refine his skills. Pankaj Mullick in particular took a keen interest in Kundan Lal and mentored him.

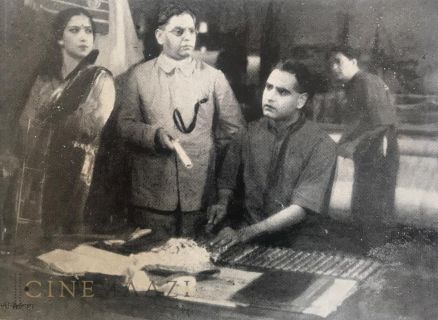

Kundan Lal debuted with Premankur Atorthy’s Mohabbat Ke Ansoo(1932), followed by Subah Ke Sitare and Zinda Laash, which released in the same year. Although these films were by no means hits, they helped Kundan Lal establish a firm footing in the film industry. Meanwhile, he continued to record his music on disks with the Hindustan Records Company of Calcutta.

Kundan Lal debuted with Premankur Atorthy’s Mohabbat Ke Ansoo(1932), followed by Subah Ke Sitare and Zinda Laash, which released in the same year. Although these films were by no means hits, they helped Kundan Lal establish a firm footing in the film industry. Meanwhile, he continued to record his music on disks with the Hindustan Records Company of Calcutta.

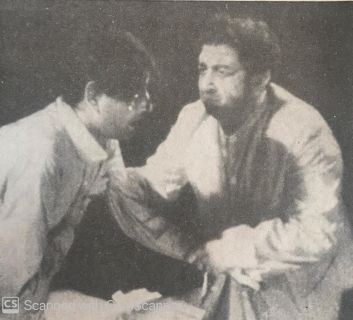

His breakthrough in the film industry finally came with his appearance in Nitin Bose’s Chandidas (1934). His performance in the film brought him the admiration he had long waited for. With his turn as the titular character in P.C. Barua’s Hindi film Devdas (1935), he became a mega star. The film was a runaway success at the box office, and earned Kundan Lal a place in Indian film history. This was not only the first Hindi adaptation of Saratchandra’s classic novel of the same title, but also a landmark experiment in combining tragedy with romance. Like Devdas himself, Kundan Lal had a troubled relationship with his father. He had no difficulty bringing the character to the screen, creating for years to come an archetype of the luckless, relentlessly tragic hero. His brooding looks, a vagrant lock of hair across his forehead, and his resonant voice filled with love and despair drove the nation into a frenzy.

Staying in Calcutta for years, Kundan Lal had also become proficient in Bengali, which enabled him to sing and act in a number of Bengali movies. He featured in a number of New Theatres’ masterpieces in both Hindi and Bengali, including Didi (Bengali)/ President (Hindi) (1937), Saathi (Bengali)/ Street Singer (Hindi) (1938), and Zindagi (1940) among others. With each film after Devdas, Saigal’s success soared to the skies. He even had the rare distinction of being the first non-Bengali singer that Rabindranath Tagore allowed to sing a song based on Rabindra sangeet. It is recorded that Nitin Bose was making a film in which he wanted to use songs based on Tagore’s writings to be sung by Kundan Lal. But he was unsure whether Tagore would permit Kundan Lal, a Punjabi lad, to sing his songs. Bose took him to Shanti Niketan to meet Tagore, who was very impressed by Kundan Lal’s singing and readily gave the go-ahead to Bose.

In 1935, Kundan Lal married Asha Rani. They had three children, Madan Mohan, Nina and Bina.

By the early 1940s, the centre of the Hindi film industry started shifting from Calcutta to Bombay. Kundan Lal’s contract with New Theatre was till May, 1944. However, B.N. Sircar permitted Kundan Lal to move to Bombay in 1941, where Ranjit Movietone signed him on for a whopping Rs. 1 lakh per annum. In the next year, he starred in Bhakt Surdas (1942) and Tansen (1943) under the Ranjit Movietone banner, both big hits that consolidated his popularity. The songs of Tansen, in particular, remain resplendent to this day. The film successfully shaped the classical and semi-classical thumris and dadras to the needs of cinema. Tansen is still remembered for Kundan Lal’s skilled rendition of Diya Jalao in Raag Deepak. Kundan Lal returned to Calcutta in 1944 before the expiry of his contract with New Theatres and acted in his last film with the studio, My Sister (1944).

By the early 1940s, the centre of the Hindi film industry started shifting from Calcutta to Bombay. Kundan Lal’s contract with New Theatre was till May, 1944. However, B.N. Sircar permitted Kundan Lal to move to Bombay in 1941, where Ranjit Movietone signed him on for a whopping Rs. 1 lakh per annum. In the next year, he starred in Bhakt Surdas (1942) and Tansen (1943) under the Ranjit Movietone banner, both big hits that consolidated his popularity. The songs of Tansen, in particular, remain resplendent to this day. The film successfully shaped the classical and semi-classical thumris and dadras to the needs of cinema. Tansen is still remembered for Kundan Lal’s skilled rendition of Diya Jalao in Raag Deepak. Kundan Lal returned to Calcutta in 1944 before the expiry of his contract with New Theatres and acted in his last film with the studio, My Sister (1944).

According to Sharad Dutt, Kundan Lal remained a humble man despite his overarching success and fame. He never forgot his roots, or his poverty-ridden past, a memory which made him generous to a fault. He always stopped his car when he saw destitute people on the streets, and even handed his coat over to keep them warm over the winters. He was so free with his cash that Kundan Lal’s wife instructed that his salary be handed over to his chauffeur.

.jpeg/WhatsApp%20Image%202020-04-04%20at%2015_54_53%20(1)__361x320.jpeg)

Unfortunately, Kundan Lal developed a reliance on alcohol when he was discarded from Dhoop Chhaon. Soon, he was unable to sing or perform without first having a drink, a habit that started affecting his health and his work. Due to excessive drinking, he started suffering from cirrhosis of the liver. As Dutt writes, with his health on the decline, Kundan Lal expressed his desire to meet Guru Ji of Noor Mahal, located near Jalandhar. Though his family was initially opposed to his wish, they relented on the condition that a trusted doctor would accompany him to Jalandhar.

Unfortunately, Kundan Lal developed a reliance on alcohol when he was discarded from Dhoop Chhaon.

Kundan Lal passed away in Jalandhar on 18 January 1947, the year of India’s independence and partition. He could not meet his Guru. He was only 42 at the time. His biggest hit, Jab dil hi toot gaya, hum jeeke kya karenge from Shahjehan released just before his death in 1946, is probably the most parodied Hindi film song of all time. In many ways, the song marked a watershed moment in the history of Hindi playback singing signalling the passing away of one era and the beginning of another as a new generation started taking over the reins of Hindi film music industry. Naushad, who composed music for the song, and Majrooh Sultanpuri, who penned the lyrics, were both newcomers then. Their fame grew in the years to come and so did the song’s popularity.

In a later interview, Naushad narrated an anecdote about the song which aptly sums up Kundan Lal’s tragic life. By the time he was to sing this song, Kundan Lal had become an alcoholic who thought he could not sing without drinking. To refute him, Naushad requested that he sing the same lines before and after drinking, from which he himself could choose the version he liked better. To his own surprise, Kundan Lal liked the version he had recorded when he was sober. When Naushad disclosed this to him, Kundan Lal told him that he might have lived longer if he had met Naushad earlier.

Kundan Lal had a unique voice and singing style that could not possibly be emulated, and a remarkable acting prowess to boot. The combination earned him a distinct place in the annals of Indian cinema. His ability to establish his own popularity and enchant the masses while relying on a classical base remains unparalleled. He was equally adept at singing bhajans, songs based on ragas, and even light-hearted romantic numbers. No doubt, Kundan Lal’s legacy has outlasted that of most of his peers.

According to Har Mandir Singh ‘Hamraaz’ and Harish Raghuwanshi, in all, Kundan Lal rendered 185 songs which include 142 film songs and 43 non-film songs. His film songs include 110 Hindi, 30 Bangla and 2 Tamil songs. In the non-film category of 43 songs comprising Ghazals, Bhajans and Hori, 37 were Hindi, 2 each in Bangla, Punjabi and Persian language which including rendering creations of famous poets like Ghalib, Seemaab, Zauq and others. Kundan Lal acted in 36 feature films – 28 Hindi and 1 Tamil. He also acted in a short Urdu/Hindi comedy, Dulari Bibi (3 reel) made in 1933.

Saigal was an institution unto himself. As Dutt writes, even Ustad Faiyaz Khan was so impressed with his rendition of a khayal in Raag Darbari that he told him: “Beta, mere paas aisa kuchh bhi nahin jisse seekh kar tum aur bada ban sako (Son, I have nothing more to offer that you could imbibe to become a greater singer).”

According to Har Mandir Singh ‘Hamraaz’ and Harish Raghuwanshi, in all, Kundan Lal rendered 185 songs which include 142 film songs and 43 non-film songs. His film songs include 110 Hindi, 30 Bangla and 2 Tamil songs. In the non-film category of 43 songs comprising Ghazals, Bhajans and Hori, 37 were Hindi, 2 each in Bangla, Punjabi and Persian language which including rendering creations of famous poets like Ghalib, Seemaab, Zauq and others. Kundan Lal acted in 36 feature films – 28 Hindi and 1 Tamil. He also acted in a short Urdu/Hindi comedy, Dulari Bibi (3 reel) made in 1933.

Saigal was an institution unto himself. As Dutt writes, even Ustad Faiyaz Khan was so impressed with his rendition of a khayal in Raag Darbari that he told him: “Beta, mere paas aisa kuchh bhi nahin jisse seekh kar tum aur bada ban sako (Son, I have nothing more to offer that you could imbibe to become a greater singer).”

Ustad Faiyaz Khan was so impressed with his rendition of a khayal in Raag Darbari that he told him: “Beta, mere paas aisa kuchh bhi nahin jisse seekh kar tum aur bada ban sako."

After Kundan Lal’s death B.N. Sircar made a documentary-feature film, Amar Sehgal (1955) based on the life and times of Kundan Lal Saigal. In this film, G. Mungheri played the role of Kundan Lal. The film had 19 songs taken from Kundan Lal’s films.

My grandparents’ generation adored him. But to me, back then, Saigal’s songs sounded so weird. I was young, just seven years old, and Saigal, who died two decades before I was born, was already a man of the distant past. His singing style was from an era I simply could not connect with. I had never imagined that years later I would take up the work of archiving Indian cinema and start appreciating his contribution to the same. As part of our archival work, I now even undertake the documentation of his life and filmography. The number of people who grew up listening to Saigal would be far from few. At Cinemaazi, we endeavour to keep KL Saigal’s legacy alive and kicking for the benefit of future generations.

It is challenging for the very young to appreciate the virtuosity of the late Kundan Lal Saigal . But, as aptly put by Shekhar Gupta in his article, Saigal’s voice tends to grew on many of us as we grow less young.

It is challenging for the very young to appreciate the virtuosity of the late Kundan Lal Saigal . But, as aptly put by Shekhar Gupta in his article, Saigal’s voice tends to grew on many of us as we grow less young.

211 views

.jpg)