A Silent Film Celebrating A Centenary: Sairandhri / सैरन्ध्री (1920-2020)

The Epic and the Epochal Memory

For an Indian silent film, this is not an ordinary centenary but epical it is. It brings to us the epic Mahabharata and one of its most significant Virata Parva, which is the fourth book of the epic narrating the story of the Pandavas’ final year of exile, when they live disguised in the city of King Virata. While they live incognito as Virata’s servants, Keechaka, the Matsyan general falls in love with Draupadi, disguised as a hairdresser (Sairandhri) to the queen Sudeshana. Realizing that the King Virata would not protect her, she convinces Bheema (disguised as a cook) to kill the lusty and immoral Keechaka. Once he is dead in a bloody duel with Bheema, the Keechaka kinsmen attempt to immolate Draupadi on the dead general’s funeral pyre. Once again Bheema goes to her rescue and wipes out the entire clan. The Virata Parva is a dramatically exciting part of the Mahabharata, consistently attracting the performing and plastic art practitioners.

“This book,” as Isabelle Onians and Somadeva Vasudeva state, “has been the subject of much debate. It has been shown to be a fairly late part of the ‘Mahabharata,’ though some of the most convincing evidence for this involves the hymn to Durga, which hardly proves that the entire book is a late addition. Regardless of when it was included in the epic, ‘Virata’ proves to be a crucially important part of the ‘Mahabharata’.” [Mahabharata, Book Four, Virāta, Tr. Kathleen Garbutt, 2006: New York University Press, JJC Foundation] As the Pandavas were on their way to Virata’s ‘pleasant city’, Vaishampayan, the narrator, mentions Yudhishthira ‘praising Durga in his mind’. There are long passages in the Book, propitiating the Goddess.

The Pandavas and their Disguises

This is how the Pandavas had disguised themselves with their new tasks and names:

1. Yudhisthira - game (chess) entertainer to the king and calls him Kanka.

2. Bheema – the cook, Ballava.

3. Arjuna, the dancer and music teacher is a eunuch named Brihannala; he clothes himself in female attire.

4. Nakula, renamed Granthika, tends royal horses.

5. Sahadeva as Tantipala herds cows, and –

Draupadi becomes Sairandhri or the hairdresser to the queen Sudeshana. Sairandhri is also called Malini. In Sanskrit, the name Malini literally means a woman who makes garlands, wife of a garland-maker or gardener, female florist. Sudeshna always addresses her as Malini as she would deck her up with flowers. Keechaka is queen Sudeshana’s brother.

Matsya Kingdom, as described in the Virata Parva, was one of the sixteen great kingdoms during Vedic era as narrated in the Mahabharata. It also appears in the Buddhist Anguttara Nikaya (6th BCE). Matsya in Sanskrit means fish, which is also one of the avataras (incarnations) of the Hindu deity Vishnu, described in detail in the Matsya Purana. The Matsya kingdoms had the fish in their state emblem.

The Book of Virata Parva has traditionally four sub-parvas or the little-books and seventy-two adhyayas (chapters / sections):

1. Pandava-pravesha Parva

2. Keechaka-vadha Parva

3. Go-harana Parva

4. Vaivahika Parva

For scenographic (including costumes, sets and general ambience) and mythographic visual references that the makers of silent films (such as Sairandhri) drew substantially from Raja Ravi Varma’s paintings widely circulated through calendars, oleographs and lithographs are quite evident in the extant silent film documents.

Sairandhri: From Litlore to Folklore to Filmlore

The Virata Parva in general, and the story of Sairandhri in particular, is part of Indian folklore as well the eventual filmlore. The Keechaka Vadha (The Killing of Keechaka) Parva is yet another story that is part of a continuing interest incorporated in Kerala’s dance traditions such as Kathakali, as also Yakshagana in Karnataka.

This is how the Kalamandalam Kathakali artistes would enact and elaborate the act of Keechaka’s lustful advances towards Sairandhri and her resistance and the subsequent entry of Bheema. The engaging dramatization through dynamically rhythmic gestures of the physical miming is quite evocative of the epic. Hailing from the land of Kathakali, Raja Ravi Varma seems to have imbibed all those colors and the dance-theatre traditions. Here is an excerpt from a Keechaka Vadha Kathakali performance:

Though the story of Sairandhri and that of the killing of Keechaka are integrally the same, they are often separated as titles of the plays and films, e.g. a 1926 silent film produced by the Poona-based United Pictures Syndicate was titled Keechaka Vadha. A decade prior to that, Nataraj Mudaliar had made the silent Keechaka Vadham (1917) for the Madras-based Indian Film Company.

%2C%20a%20book%20in%20Gujarati%20by%20Vinod%20Joshi%2C%202018%3B%20cover%20page%20(designed%20by%20Kushagra%20Joshi)%2C%20pc%20author%E2%80%99s%20collection_.jpg/Sairandhri%20(Prabandha%20Kavya)%2C%20a%20book%20in%20Gujarati%20by%20Vinod%20Joshi%2C%202018%3B%20cover%20page%20(designed%20by%20Kushagra%20Joshi)%2C%20pc%20author%E2%80%99s%20collection___435x600.jpg)

Besides literature, what is interesting is the way the early (1920s) theatrical plays incorporated contemporary political or social commentaries couched in mythology, the way Jatra in Bengal or Bhavai in Gujarat would do in their narrative pliability. For instance, the Marathi playwright Krishnaji Prabhakar Khadilkar (1872-1948) would satirize Lord Curzon in his play Keechaka Vadha in the 1920s. Lord Curzon served as Governor General and Viceroy of India (1899-1905). His policy resulted in deep discontent and the upsurge of a revolutionary movement in the country. He was quite unpopular as Viceroy of India. The play was banned by the British Government.

This cover page of Khadilkar’s published Marathi play Sangeet Draupadi shows the author’s proflicity in playwriting (and proclivity towards the epic persona of Draupadi) that were staged in Maharashtra, including the banned Keechaka Vadha.

Obviously, the Mahabharata’s Virat Parva has a tremendous dramatic potential that had comparatively attracted playwrights and folk theatre artistes more than the filmmakers, both in the silent and the talkie eras. Nevertheless, it would be very pertinent to talk about the century-old silent film Sairandhri which, without its prints extant, provides some fascinating insights into its, as well as its maker’s history, through some written accounts and visual evidences. Sairandhri, the silent film, was an instant hit not only because of its magnificent sets but also because it had starred the real female persona and not males impersonating as females.

Cinemaazi takes the lead in celebrating the centenary of this silent film Sairandhri (1920-2020) and recreating the visual narratives out of extant pictorial and published material on a broader pan-Indian span.

Sairandhri, the film, the maker and the story of its making

The 1920 film Sairandhri was directed by the genius of Baburao Painter, under the banner of his Kolhapur-based Maharashtra Film Company. The film was called Sairandhri and our Cinemaazi story is about this Virata Parva’s fascinating episode. The film was released on 7 February 1920 not in Kolhapur or Bombay but in Poona, at the Aryan Theatre (reportedly established in 1913, it is no longer extant).

But with the covert complicity of his sister, the queen Sudeshana, Keechaka begins to molest Sairandhri who had, in the meantime, already informed Bheema and they hatch a plot to lure Keechaka to the King’s court. Blinded by his lust and arrogance, Keechaka remains irreverent to Sairandhri’s pleas. Bheema enters and ferocious wrestling combat takes place between the two mighty bodies. Ultimately, Bheema overpowers Keechaka and finishes him off.

The Maker of Sairandhri: Baburao Painter (1890-1954)

Born Baburao Krishnarao Mestry in Kolhapur, he was a self-taught painter that eventually became his family name. He was also a sculptor, following the academic art school style. Between 1910 and 1916, Baburao and his cousin Anandrao were the leading painters of stage backdrops (drop scenes) in Western India doing numerous works for Sangeet Natak troupes and also for Gujarati-Parsee theatres. In early years of his life (around 1910), Baburao was associated with a family-run photo studio in Bombay. Once Dadasaheb Phalke’s silent feature film Raja Haishchandra was released in 1913, both brothers got ardently attracted towards the art and craft of motion pictures. They went to Mumbai’s chor bazaar (flea market) and bought a movie projector and began to exhibit films in Kolhapur while also studying the techniques of motion picture making.

%20kept%20painting%20while%20making%20films%20too.jpg/Baburao%20Krishnarao%20Mestry%20(Baburao%20Painter%2C%201890-1954)%20kept%20painting%20while%20making%20films%20too__600x466.jpg)

Kolhapur, the hub of wrestling schools and the Maharashtra Film Company

In September 2018, I was in Kolhapur for over ten days with my German filmmaker friends who were making a documentary film on Taalims (as the Kushti akharas are so called locally) and the Kushti players who are still engaged in ‘maati chi kushti’ or traditional mud wrestling. For encouraging and sustaining this great kushti tradition the main credit should go to Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj of Kolhapur (1874-1922). The actors Balasaheb Yadav and Zunzarrao Pawar who essayed the roles of Bheema and Keechaka in Sairandhri (1920) were professional wrestlers from Kolhapur. In fact, V. Shantaram, who joined the Maharashtra Film Company, just when Sairandhri (1920) was completed and was, being released, had learnt the art of wrestling under Balasaheb Yadav, during his school days.

While in Kolhapur I had visited the sites of the three historic film studios, viz. (a) Maharashtra, (b) Jayaprabha, and (c) Shalini. The studio set up by Baburao Painter is not extant now, but there is a memorial dedicated to it and to its founder as seen in the picture above. Set up in 1918-1919, the Maharashtra Film Company was an excellent training institute where future filmmakers and technicians such as V. Shantaram, V.G. Damle, S. Fattelal and others were apprenticed and graduated to set up yet another historic film company / studio, Prabhat Film Company in Poona / Pune. Historically, the credit for creating such a glorious history goes to the Guru Baburao Painter of Kolhapur’s Maharashtra Film Company.

The entire studio of the company in Kolhapur was run by the permanent staff of only fifteen in number, who was on its payroll. Baburao Pendharkar, a lead actor and the right-hand man of Baburao Painter’s earned Rs. 25 as his monthly salary. Related to V. Shantaram, Pendharkar was instrumental in helping the former join the Maharashtra Film Company as a permanent employee.

Here is an unconfirmed silent footage shot in Kolhapur attributed to Baburao Painter; it is quite plausible that he had shot this footage since by this time he had finished assembling his motion picture camera, which he might have put to a trial run.

The Making and the Release of Sairandhri (1920)

Those days the city of Kolhapur had no electric supply, hence the silent film Sairandhri was shot in the day light; during monsoon, most of the time the shooting would stop in absence of the sun in the sky. Sairandhri was shot in one of the brighter rooms with reflectors.

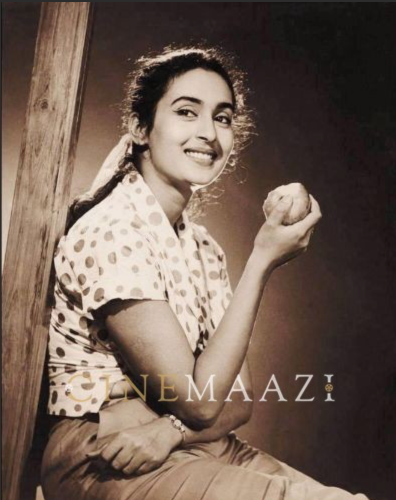

For Sairandhri, Painter introduced female artistes, Gulabbai and Anusuyabai, who were given the screen names of Kamala Devi and Sushila Devi, respectively. Since acting as an occupation for women was looked down upon and socially tabooed those days, both these women were ex-communicated by their communities and had to find refuge in the studio premises. Apart from acting in the film, they would also cook and serve food to the unit.

%2C%20pc%20author%E2%80%99s%20collection_.jpg/Kamala%20Devi%20and%20Sushila%20Devi%20in%20Baburao%20Painter%E2%80%99s%20silent%20film%20Sairandhri%20(1920)%2C%20pc%20author%E2%80%99s%20collection___436x600.jpg)

Special Effects and Designing of Costumes and Sets

The film had employed some brilliant special effects, e.g. when Bheema wrenches the head off Keechaka’s bleeding torso and holds it afloat. In his Marathi autobiography Shantarama, V. Shantaram describes this scene and Baburao Painter’s genius in filmmaking. Painter also designed the sets of his films in collaboration with the skills that V. G. Damle and Sheikh Fattelal had acquired under Painter’s tutelage. [The same Damle-Fattelal duo later made the immortal Marathi film Sant Tukaram (1936) for Prabhat Film Company in Poona / Pune.]

Baburao Painter changed the concept of set designing from painted curtains to solid multidimensional lived-in spaces. He was also a pioneer with many other aspects related to filmmaking, distributing and exhibiting. For example, he was the first to issue program booklets, complete with photographs and details of the film. He painted the eye-catching posters of his own films as I have previously cited the example of his film Kalyan Khajina.

Such is the charismatic story of the silent film Sairandhri which completes its centenary in the year we spend confined in our homes – corona-virus has its own ways to operate when even the wrestling Taalims in Kolhapur have to close down… But the cruel Keechaka’s scream are heard even after a centenary of his being there on the screen via Baburao Painter’s ‘silent’ film Sairandhri! It is not a One Hundred Years of Solitude….

Postscript:

As a PS let me entertain you with this excerpt from a hit Telugu film called Nartansala (The Dance Pavilion) which was an adaptation of the Mahabharata’s fourth book Virata Parva I had launched my story with for celebrating the centenary of Sairandhri (1920-2020). The 1963 Telugu film stars NTR (1923-1996), Savitri (1936-1981), S.V. Ranga Rao and Dandamudi Rajagopal in the lead roles, among others. Here is the fight scene between Keechaka and Ballava (Bheema).

Written by Samudrala Raghavacharya (1902-1968), the film was directed by Kamalakara Kameshwara Rao (1911-1998). Shot at the Vauhini and Bharathi studios in Madras, the National-Award winning film was also dubbed in Bengali and Odia languages.

Sairandhri of 1920 from Kolhapur has travelled through lands and languages while at the top of the tripod, Baburao Painter’s ‘swadeshi’ camera still narrates the history of Indian cinema. Painter hasn’t given up his paintbrush nor has he lifted his hand off the camera handle. He has already busied himself with making yet another silent feature Surekha Haran from the Mahabharata…

Amen!

Tags

About the Author

Amrit Gangar is a Mumbai-based film theorist, curator, historian and author. He writes both in Gujarati and English and has been widely published. Two of his Gujarati books on cinema have won the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi’s awards. He was the Consultant Curator to the National Museum of Indian Cinema, Government of India, located in Mumbai. He has presented his theory of Cinema of Prayoga at various prominent venues in India and abroad, including the Tate Modern, London; the Pompidou Centre, Paris; Lodz Film School, Poland; Santiniketan, India, et al. He was Indian contributor to the Film International published from Tehran, Iran and the bilingual (English / Japanese) ART iT, published from Tokyo, Japan.

Gangar has been the curator of film programs for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Kerala; the Kala Ghoda Artfest, Mumbai; the Mumbai International Festival for Documentary, Short & Animation Films; the Danish Film Institute, Copenhagen, etc. Besides Walter Kaufmann, he has also written books on Franz Osten (Bombay Talkies) and Paul Zils (one of the founders of the still active Indian Documentary Producers’ Association), both film directors from Germany. His book Chalchitra / Chhalchitra has been published by the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi, Gandhinagar. He was also active in Indian film society movement and headed the Mumbai-based film society Screen Unit that has published two major books on Ritwik Ghatak.

Over the years, Gangar has worked on productions of numerous European and Scandinavian films and video installations, including Lars von Trier and Jorgen Leth's Five Obstructions. He is an Adjunct Professor at the IDC-IIT Bombay.

.jpg)