A Lesson For The Producer

Everytime I sit in my office and face a number of producers who have come to tell me of their woes in my mind float a hundred faces, of many friends who were once well known film-makers and who are now forgotten-whose talent has been lost to his industry, who have gone out of business or are in the process of going. And it occurs to me that perhaps, the natural, destined fate of every producer is total bankruptcy.

It is inevitable in this game of show business that every staggering burst of prosperity should ultimately dwindle into a thin ray of hope that is one day lost in this sea of darkness.

Therefore, it pains me immensely to see that, instead of doing something to dodge their inevitable doom and exile from show business, most of the film producers, in their brief moments of triumph and glory try to assert their own ego and see themselves in the image of great crusaders, reformists and born leaders and, in the process, face each other with hostility and suspicion. They forget that, in this revolving merry-go-round, each one faces the sun for a small moment and then moves on to yield the place and the view to someone else.

Those who foolishly believe at that moment that they alone have the monopoly of the sun soon learn the bitter truth that, in show business, the past is soon forgotten, the present is never accepted as the final truth and the future is always dark.

I do not wish to sound pessimistic for I do believe that films in India have yet much greater heights to scale and offer a tremendous scope for men with vision and talent. But I also do believe that the repeated crises and rifts within the ranks of filmmakers result primarily from people giving too much serious attention to trivialities and forgetting to place the things in their correct long-term perspective. People are so apt to be carried away by the heat of the moment and so overawed by their personal glory or personal problems-both of which do not last very long-that they regret to take notice of the basic and fundamental issues at stake.

First of all, there are director-producers - directors who become successful and turn producers so that they should not have to work for someone else's profits. (Often, when directors turn producers, the profits stop up but that is a different matter).

Then there are broker-distributor-producers - producers who have something to do with the distribution market and with their contacts are able to sell their pictures in advance. The usually to not make films-they make "propositions." These "propositions" are excellent plans on paper but usually make very poor films.

A third category is to financier-producers - financiers who either produce films directly or get them made for them indirectly by becoming world right controllers or "the party with the first lien on the film and its positive and negative prints." They are usually the least interested in the development and growth of the film industry, as a racecourse punter is not interested in the well being of the horses that run for him-he is concerned only with his own profit and loss.

Then there are writers-turned producers, music directors-turned producers and stars turned-producers sometimes, even a cameraman or an art director-turned producer. This they do either to help a relative or to stabilise either own market prices or, sometimes, for the chief purpose of staging a "come-back". But this category I dismiss as of no importance because with them film- making is more of a hobby which sometimes pays very good dividends but often results in heavy losses.

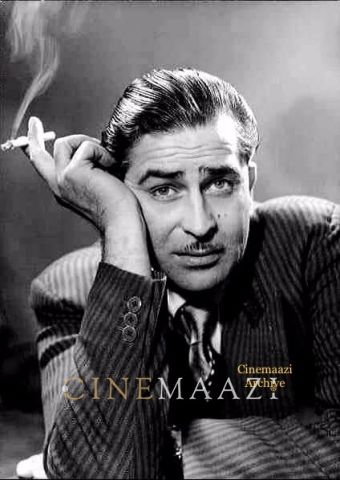

.jpg/B_N__Sircar_(vers_1940)__357x480.jpg)

Now that we have classified producers, we must use this classification to analyse the present ills of the film industry. Most of the producers are director-producers or producer with no finance of their own and hence they have to depend on their good relations with stars and music directors to be able to continue in the business. This has led to the monopoly of six or seven stars, two or three music directors and two or three playback singers. Because most producers have no star potential they are playing a losing game. They are not able to have at their disposal storehouse of self-generating talent and, consequently, then one or two pictures or theirs flop, the big stars and music directors refuse to work for them except for fabulous prices. Then that is the beginning of their end.

But the psychological reaction that sets in after the failure of their films leads to very interesting results. There is so much talk of "purposeful films" and "progressive film" and "educational films" but, actually, there are only two categories of films and successful films, just as there are only two kinds of novels that are written, those which are read and those which remain unread and unsold on the booksellers' shelves.

In India, "unsuccessful" film producers have sought solace in claiming that they make films not to earn money but to "educate" people. It is a wonder that people who have themselves crossed matriculation examination with great difficulty, have not taken upon themselves to educate the people. But, ultimately, unless the producers get together and break the monopolies of a few stars, music directors, singers and technicians, there can be no permanent solution to the ills of the films industry.

The clash of ego that has today resulted between award winners and those who have not won any award is really a clash between 'haves' and "have nots," the former forgetting that in the film industry there is very little difference between the two, and the "haves" can become "have nots" and vice versa in no time. As I have said before, there are only two kinds of films, successful and unsuccessful. And, as long as, most producers remain unsuccessful and we do not do anything to ensure a reasonably secure and profitable future for most of our film-makers, the present frustration, leading to internal dissensions and mutual mud-slinging will continue. Neither awards, genuine or false, nor party politics can for long save a film producer from this traditional doom. Now is the time to act-to strike unitedly at the very root of the causes that have brought untold trouble to our industry and persuade the Government and create our own pool of new and abundant talent to ensure a bright future for the Indian cinema. Producers-the big, little men of out film industry-should be guaranteed a life-time of two square meals a day while they are venturing into multi-million star-studded films for the benefit of their stars and musical directors and the Government exchequer.

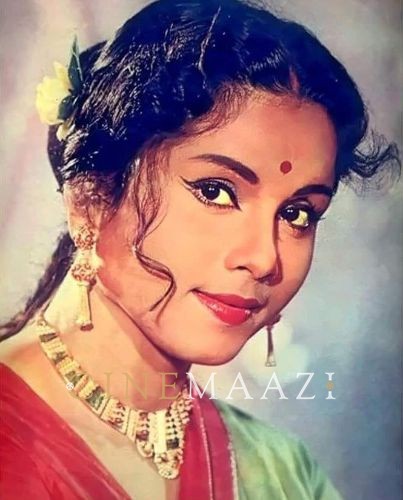

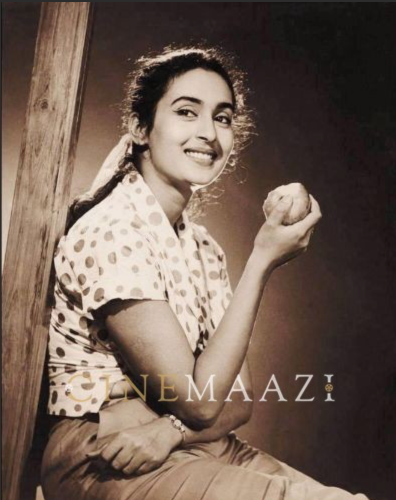

This article was originally published in Film Industry of India which was compiled by B K Adarsh in 1963. The images used were not part of the original article.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)