This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $3700/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

It was 1996 when my parents’ wedding was fixed. As is the case with most Indian marriages, it was not just my parents getting married, but their families too.

Exuberant Punjabis from my father’s side of the family met equally enthusiastic ones from my mother’s. In the midst of chaotic exchanges and wedding preparations, they were hit by a surprising realisation: several years ago, both families had known each other and often frequented each other’s homes.

My Dadu fondly recalled “Bekal Chachaji”, a close friend of his father’s and a talented palmist. “Bekal Chachaji” also happened to be my Nani’s father who had passed away in 1982, leaving behind a family that missed him every day.

The bond between my parents’ families strengthened with this realisation, and an unexpected connection was formed.

As a result of this connection, I grew up hearing stories about my great-grandfather or Bade Nanu from both sides of the family. I never had the chance to meet him, but he still felt like a constant presence in my life, always looking out for me.

The majority of these stories came from my Nani, who would tell me about his contributions to the freedom struggle.

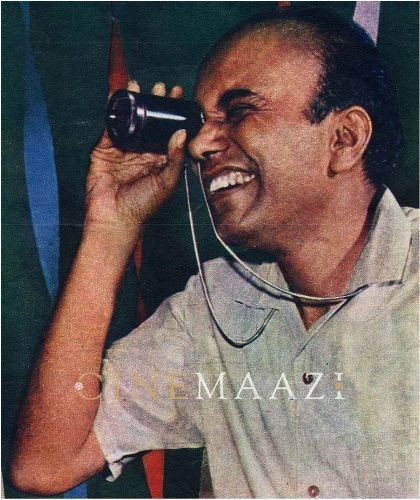

Jailed by the British at 19 for his fiery, nationalistic poetry, Bade Nanu – or Bekal Amritsari, as the world knew him – was surrounded by fellow freedom fighters in his prison cell in Lahore. They scrambled to hear his poetry, surrounding him eagerly as the words flowed from him. He was a born performer, people said, giving him the title of stage da maalik or “owner of the stage.”

My Nani would tell me how Bade Nanu had been a freedom fighter, a poet, a film director, a screenplay writer and a lyricist. He also had the title of Gyani, the equivalent of a PhD in Punjabi language and literature, and was fluent in Punjabi, Hindi and Urdu.

As a child, it fascinated me that someone could do so many things at once. I would listen, awestruck, hoping that one day I would be able to become a person that Bade Nanu was proud of. Even as an adult, when people tell me I’m following his footsteps, a strange sort of happiness bubbles up in my chest.

Born in Amritsar, Punjab on the 16th of April, 1917 as Baldev Chander Arora, Bade Nanu took the pen name “Bekal” meaning “restless” when he first started writing.

Writing was in his blood – he was the nephew of the legendary Punjabi poet Dhani Ram Chatrik, and his younger brother J.D. Mastana was also a writer, famous for his play Preeto.

In the preface to his book Bekal de Geet, Bade Nanu wrote, “Writing songs every day comes as naturally to me as talking to my baby daughter, Poli.”

With his family, he also ran the Bekal Book Agency in Amritsar.

.jpg/Portrait%20(Young)__360x480.jpg)

Bade Nanu was an exceptional performer, and – though he never pursued a career in singing – a talented vocalist.

Right from the first time he stepped on stage, only a teenager, to recite his poem Piya de Joghan, he captivated the audience, reducing them to tears – an incident fondly remembered by his mentor and college principal S.S. Amol.

His uncle Dhani Ram Chatrik wrote about him, “Bekal has gone through a lot, and circumstances led him to grow up fast. His talent is more than his age. I have always been able to write, but he roars like a lion when he is on stage.”

Even in Bade Nanu's later years in Mumbai, his children recall, he was invited to kavi sammelans and gurudwaras everywhere, especially on the Sikh occasions of Guru Nanak Jayanti and Baisakhi.

Arshi Darshan was Bekal Amritsari's anthology of religious poetry. Released in 1938, new editions of the book were republished for the next five years due to its wide popularity.

Jeevan Lehra (1940) was a collection of poems he had performed on stage. The poems documented the ups and downs of his life until then.

Bekal de Geet and Satrangi Peenga were also anthologies published by Bekal Amritsari – but there are possibly more books that have been lost with time.

Additionally, in the preface to Bekal de Geet, Bade Nanu mentioned how the high cost of paper prevented him from publishing many other books he had written.

Unfortunately, his works have now faded into obscurity, only remembered by a select few.

Bekal Amritsari's film career started in 1940 in Lahore with the now lost Punjabi films Laila Majnu and Mera Punjab, for which he wrote every song.

In his book Bekal de Geet, Bade Nanu mentioned how so many struggled to get into the film industry, but the opportunity fell into his lap when he received a telegram from the East India Film Company, inviting him to Kolkata to work on the discography of several movies.

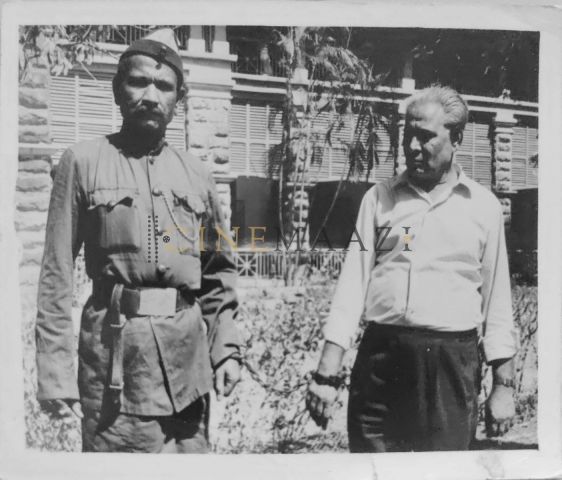

%20and%20Brothers.jpg/With%20Chaman%20Nillay%20(Sherni)%20and%20Brothers__600x451.jpg)

He spent the next couple of years travelling between Kolkata, Amritsar and Lahore, working on songs for several movies such as Mera Mahi (1941), Gowandhi (1942) and Jawab (1942).

It was in Kolkata that Bekal Amritsari was acquainted with celebrated singer and actor K.L. Saigal. They developed a close friendship, and K.L. Saigal, impressed by Bade Nanu's writing, asked him to write songs for him in Punjabi.

The result was two tunes – Woh Sahne Sakhiya Meri and Mahi Naal Je – that ended up being the only songs that K.L Saigal ever sang in Punjabi.

Years later, my Nani's sister remembers one of these songs playing on the radio as she sat next to her father. As the track came to an end, the anchor explained that the writer of the song was unknown. Earnestly, she turned to her father, asking him to call the radio station and tell them he was the writer.

It was in Kolkata that Bekal Amritsari was acquainted with celebrated singer and actor K.L. Saigal. They developed a close friendship, and K.L. Saigal, impressed by Bade Nanu's writing, asked him to write songs for him in Punjabi.The result was two tunes – Woh Sahne Sakhiya Meri and Mahi Naal Je – that ended up being the only songs that K.L Saigal ever sang in Punjabi.

But Bade Nanu simply shook his head. K.L. Saigal was gone, he said, and he had done what he had wanted to do. It was not Bade Nanu's place to make himself known if that wasn't what Saigal had chosen.

K.L. Saigal, for his part, had in fact sung the name Bekal in Mahi Naal Je to show his affection for Bade Nanu.

Bade Nanu's film career continued to grow, and he began to write screenplays as well as co-direct movies.

He moved to Mumbai in the late 1940s, and worked on several movies such as Miss Coca Cola (1955), Hazaar Pariyan (1959), Do Behnen (1959) and Kiklee (1964).

1962's Chaudhry Karnail Singh, with a screenplay and eight songs by Bekal Amritsari, was the first Punjabi Film to receive a Certificate of Merit from the jury of National Film Awards.

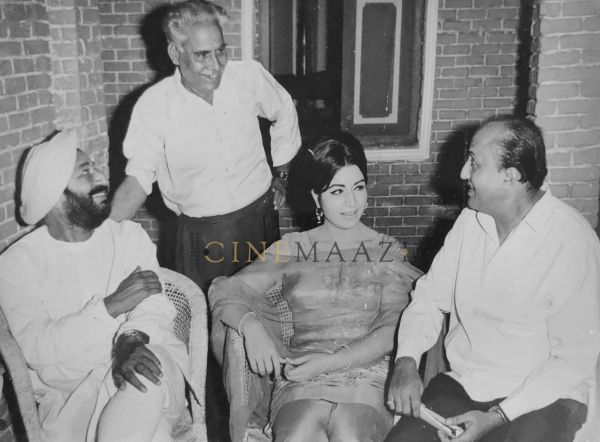

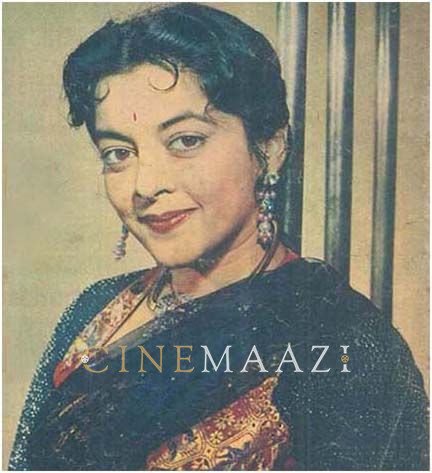

In his expansive career in the film industry, Bade Nanu worked with many well known talents such as Shammi Kapoor, Mohammed Rafi, Shamshad Begum, Geeta Dutt, Prem Chopra, Tun Tun, Nargis, Madan Puri, Sulakshana Pandit and Geeta Bali.

1962's Chaudhry Karnail Singh, with a screenplay and eight songs by Bekal Amritsari, was the first Punjabi Film to receive a Certificate of Merit from the jury of National Film Awards.

Lady Robinhood (1959) was the last Hindi movie that Bade Nanu wrote songs for – following which, he began to work on his passion project, the renowned cult classic Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai (1969).

Very early on in his writing journey, Bade Nanu had said that his pen was meant to serve Punjabi and the Sikh religion.

Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai was a testament to this: released on the 500th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak, it was Bekal Amritsari's masterpiece. From the idea of the movie to its screenplay and direction, Bade Nanu was deeply involved in Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai and its creation.

He was the first and only person to receive permission to film inside the Golden Temple after spending a considerable amount of time explaining the plot and aim of Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai.

The movie also featured appearances from a young 14th Dalai Lama, and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (famously known as Frontier Gandhi).

Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai's message was not just religious, but moral – it focused on virtues like love, honesty and forgiveness, with the plus point of a riveting plotline.

Starring Prithviraj Kapoor and Suresh, the movie was an instant hit, and ran housefull for weeks. Such was its impact on both Punjabi cinema and audiences that people would take their shoes off and cover their heads before entering the cinema hall, and toss coins at the screen.

Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai was the first Punjabi film ever to receive the National Film Award – an honour that only 12 Punjabi movies have received till date. It also received the Filmfare Award for Best Story and Dialogue.

After Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai, Bade Nanu retired from the film industry, deciding to dedicate all his time to his family, writing and other hobbies.

In his personal life, Bekal Amritsari enjoyed gardening. He was also a brilliant palmist, but did not practice palmistry commercially – it was only his family and close friends that knew of this talent.

Bade Nanu did not believe in bringing his work home. There are rare instances of this that his children remember – the Amritsar premiere of Kiklee, a visit to the set of Chaudhry Karnail Singh where my young grandmother was terrified of famous villain Prem Chopra as her father laughed, and Indira Billi falling off a chair – are a few of the incidents they remember.

Without exception, the people who knew Bekal Amritsari describe him as warm and jovial. He could brighten up any room he walked into with just a few words.

Bade Nanu did not believe in bringing his work home. There are rare instances of this that his children remember – the Amritsar premiere of Kiklee, a visit to the set of Chaudhry Karnail Singh where my young grandmother was terrified of famous villain Prem Chopra as her father laughed, and Indira Billi falling off a chair – are a few of the incidents they remember.

At kavi sammelans with his wife, he would start his performances by greeting the audience with a “Save for one: brothers and sisters”, earning laughter and appraisal.

His children recall how he never got angry, and was always gentle and careful with his words.

They remember history lessons with him, when he would assign a different historical character to each of his six children and write them dialogues to remember. As a result, they were able to memorise every little fact in their textbook, and Bade Nanu was able to expand his own knowledge of history.

Another thing they remember with affection is how he would call them all to his room after he finished writing something, and ask them to freely criticize it so he could improve.

On the 16th of April, 1982, when my mother was only 8 years old, her family attended a wedding.

Bade Nanu stayed home, and while going back home from the wedding, my mother insisted on wishing him a happy birthday. She was deeply attached to her grandfather, and still recalls sitting with him at the table, trying to imitate the seriousness with which he wrote.

A few hours after she wished him, Bade Nanu passed away from a heart attack. It was his 65th birthday.

During the Chautha, one of his friends informed the family that Bade Nanu had also had a silent attack on a film set a few years ago. He had been rushed to the hospital, and insisted that no one tell his family about the health scare because he didn't want to worry them.

It was the very essence of Bade Nanu: he cared about goodness, about family and freedom and love. Those were the values he stood for again and again and again, and his writing was just a way to express these ideas.

Today, Bekal Amritsari's legacy has faded, his name forgotten. He has become just another man in the endless list of people who made Bollywood what it is.

It was the very essence of Bade Nanu: he cared about goodness, about family and freedom and love. Those were the values he stood for again and again and again, and his writing was just a way to express these ideas.

Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai was re-coloured and re-released in 2019, without contacting or informing his family, who found out about this development through articles in the newspaper.

Even without directly being in my life, Bade Nanu has changed me in infinite ways. Every day, I work to be a great-granddaughter that he would be proud of. My family and I work for his legacy, for him to get the credit and recognition he deserves.

Every story I hear about Bade Nanu makes me respect him more. I wait and wait for the ball to drop, terrified that I will learn something that will make him less perfect to me – but it never happens.

Because that's what Bade Nanu was: he was a good person, through and through. It was this goodness that attracted people to him all his life, and it is this goodness that makes them remember him after.

Sources:

Gajendra Khanna's Video: Remembering Bekal Amritsari Ji

Asha Kathuria

Kishan Kumar Arora

Usha Binju

Shashi Mehra

Davinder Arora

Kiran Rawal

Shubh Gupta

Kitab Trinjan

.jpg)