The racial politics of the classic Tarzan movies are so notoriously retrograde that to call them racist could hardly be considered PC. Given this, it is surprising to see how readily the character has been embraced by foreign (read: non-white) filmmaking cultures outside of Hollywood, with India most frequently playing host to the esteemed ape-man.

From Superman to Zorro to James Bond, India’s B movie industry has, throughout its history, acted as something of a weigh station for beloved fictional characters making their rounds through the bustling marketplace of world popular culture. Why Tarzan should be the most revisited of these characters—with India alone making upward of forty Tarzan films over the last seventy years—is perhaps a result of him presenting a blank slate ideal for both audiences and artists to project their desires upon.

‘Many women would delight in living like Eve – if they could find the right Adam!”

This furtive salaciousness may be part of the Tarzan mythos’ appeal to Indian filmmakers. The American Tarzan films had for years reliably provided their audiences with glimpses of naked female flesh in more conservative times. 1934’s Tarzan and his Mate, released just before the implementation of the Production Code, even gave viewers a brief, unobstructed view of actress Maureen O’Sullivan’s pubis. Bollywood, long engaged in a cagey game of hide-and-seek with propriety, followed suit by using their Tarzan movies as license to drape its most beautiful actresses in the tiniest of leopard print bikinis and send them swinging back and forth above the camera. Later, Z-grade exploitation films like 1990’s Jungle Love (billed as a “Tarzan and Jane” story despite its main characters being named Raja and Rita) even permitted for the occasional nip slip or camel toe.

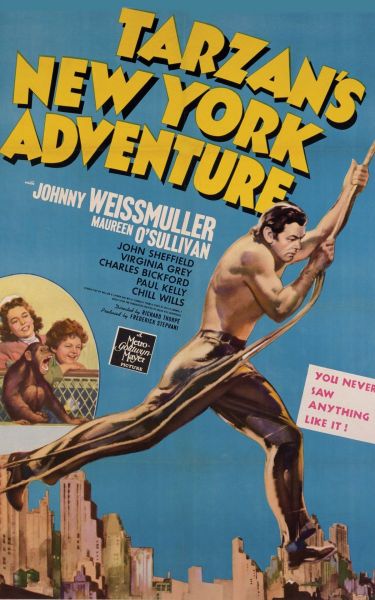

“We’re going into places where men’s minds are more tangled than the worst underbrush in the jungle. And I’m afraid… more afraid than I’ve ever been in my life. Everywhere we’d be met with lies and deceit. Your honesty and directness would only be handicaps. It would break my heart to see your strength and courage caught in the quicksand of civilization”.

It’s a heavy statement, especially leading into a film that consists largely of scenes of Cheetah wreaking havoc in toney Manhattan boutiques.

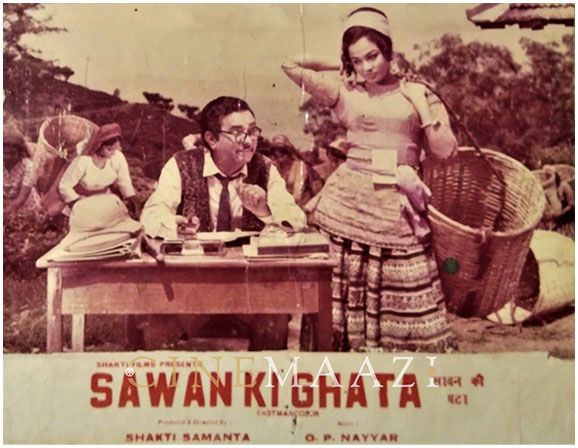

The same message is driven home in Kedar Kapoor’s virtual remake of that film, 1965’s Tarzan Comes to Delhi, starring wrestler Dara Singh as Tarzan. As in the first film, Tarzan goes to the big city to retrieve an artifact stolen by nefarious profiteers, except that, in Delhi, the threat to Tarzan’s innate purity comes less from gun toting mobsters than it does the temptations of big city life in the persons of gorgeous costars Bela Bose, Laxmi Chhaya and Mumtaz.

Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs was born in Chicago in 1875. A sickly youth, he was far from the paragon of fitness and masculinity that his most famous creation embodied. Unsurprisingly, he yearned for adventure nonetheless. As a young man, he enlisted in the US Cavalry, only to be rejected because of an undisclosed heart ailment. He spent most of the next decade pursuing an assortment of unfulfilling occupations, ranging from pencil sharpener salesman to office clerk.

Then came the day when he stumbled upon a copy of the pulp magazine All Story Magazine. He later remarked that "if people were paid for writing rot such as I read in some of those magazines that I could write stories just as rotten." The magazine paid him $400 for his first story Dejah Thoris, Martian Princess.

Burroughs’ first novel, Tarzan of the Apes, was serialized in All Story in 1912 and went on to become a sensation. To his credit, Burroughs was ahead of his time in understanding the importance of licensing; he became a wealthy man from the royalties accrued from countless Tarzan toys, comic strips, radio dramas, etc.—and, of course, movies.

Tarzan’s film debut, Tarzan of the Apes, was released by First National Exhibitors Circuit in 2018. The film, which starred muscleman Elmo Lincoln as adult Tarzan and charismatic child actor Gordon Griffith as Tarzan’s younger self, was filmed in the swamps of Morgan City, Louisiana and in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park. It is widely considered to be the most faithful adaptation of Burroughs’ novel, with one notable exception; the inclusion of a British sailor character who not only saves Tarzan’s parents from the mutineers, but also teaches the young Tarzan to read and ultimately is responsible for bringing Jane Porter and her family to the jungle (in other words, he’s a kind of narrative calk to be used by the screenwriter whenever he encounters a plot hole).

In addition to some cosmetic differences (Elmo Lincoln’s version of Tarzan is a lot less clean-cut than later versions and has a tendency to smile maniacally), Tarzan of the Apes dutifully rolls out all of the expected particulars of Tarzan’s origin story. The British lord Greystoke is dispatched to Africa to “suppress” the activities of Arab slavers there. On the ship over, the crew stages a mutiny, leaving the lord and his pregnant wife stranded on the African coast. Soon thereafter the child is born and is later stolen by a tribe of apes trying to replace the deceased baby of their queen. The apes and the queen raise Tarzan as their own and he quickly begins to see himself as one of them. Some odd years later, an expedition to find Tarzan, led by Professor Porter, arrives on the beach. Porter has a beautiful daughter named Jane, whom Tarzan is immediately smitten with. Overcome by his primitive urges, he snatches the girl and takes her back to his treehouse, where romance improbably blossoms.

While Tarzan of the Apes does play on the sexual threat that Tarzan poses to Jane, it lets us off the hook when Tarzan, trying to reassure a frightened Jane, says, “Tarzan is a man, and men do not force the love of women.”

Aside from that, the film features a lot of the things that we’ve become used to seeing in Tarzan movies:

Lots of stock footage of animals, people in ill-fitting ape costumes, an outsider villain callously laying waste to the jungle and its people (The Arab slavers); and, in the original cut, lots of documentary-style nudity (most of which was edited out of later versions). You’d think that there would be an elephant stampede, but given that First National chose to serialize the novel over the course of consecutive films, I’m assuming that’s in at least one of those.

The film was a big success, taking in over three million dollars in the U.S. alone – of which Burroughs, who had licensed the book to National for an unheard of five thousand dollars, probably took a healthy cut. Elmo Lincoln went on to make four more films in the series before leaving off to find different kinds of roles. After that, the remaining years of the silent era was a period of peak Tarzan. Producer Sol Lesser launched a competing series starring future-Flash Gordon Buster Crabbe and Universal kept their version alive with Frank Pierce and Herman Brix respectively filling the title role.

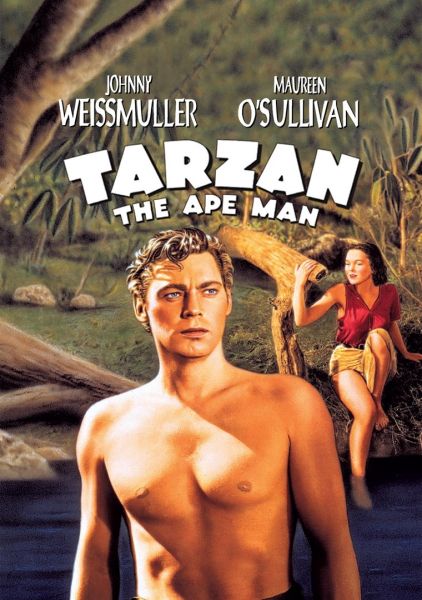

Though it is marred by the white supremacist assumptions of its time, Tarzan the Ape Man is a handsome and well-appointed film. Both Weismuller and O’Sullivan were at their primes, beautiful and lithe. It’s no wonder that a lot of people just wanted to see them get it on. At the same time, great care was taken to insure that the jungle scenes felt authentic, to the extent of featuring live animals on set with the actors (Weismuller only; O’Sullivan and co-star Neil Hamilton—yes, Commissioner Gordon from Batman—are usually pictured in front of a rear projection screen and probably never left the safety of Los Angeles.) Though those scenes were shot in Culver City and at Toluca Lake, Clyde De Vinna’s expert cinematography lends the available foliage a haunting depth and lushness, while blending nicely with the few examples of stock footage, which were taken from W.S. Van Dyke’s previous film, Trader Horn.

Tarzan the Ape Man became the biggest hit of the 1932 moviegoing season, pulling in 2.8 million dollars worldwide. Weismuller went on to star in six more Tarzan films for MGM and another six for RKO before abandoning the role in 1948. As is common with the late entries in a long series, the RKO Tarzan films arc toward the absurd, reaching their nadir with 1948’s Tarzan and the Mermaids.

Given Hindi cinema’s recent alacrity in churning out Indian versions of Hollywood blockbusters, it’s surprising that they didn’t jump on the Tarzan bandwagon until 1937. That is perhaps an indication of how much cross-pollination in international pop culture has accelerated in the internet age. Anyway, Homi Wadia’s Toofani Tarzan, starring Parsi bodybuilder and stuntman John Cawas was worth the wait. it is a debut to be remembered.

First off, it’s important to note that the Tarzan of Toofani Tarzan is a native Indian who roams the jungles of India. This homegrown take requires that certain adjustments be made to the characters’ origin story. Here Tarzan, born Leher, is the son of an Indian scientist who has just invented an immortality serum. When marauding lions attack their jungle compound, his father puts the formula in a locket around Leher’s neck and dispatches his ape-like caretaker Dada (stuntman Boman Shroff in blackface) to take him to safety. Dada places Leher and his puppy, Mothi (credited as “Prof. Motee”) in a waiting hot air balloon, then jumps in himself and takes off. Leher’s mother, Uma (Nazira), having seen her husband killed by one of the lions and her only child disappear into a stormy sky, goes stark raving mad and runs off into the jungle, only to emerge periodically throughout the rest of the film to issue one hair-raising proclamation after another.

Fifteen years later, Leher’s grandfather arrives in the jungle village of Vanrajpur in hopes of finding him. There he meets Beharilal (Chandrashekar), a shifty character who claims to be searching for “the Elixir of Youth.” Beharilal takes an immediate liking to grandpa’s adopted daughter, Leela (Gulshan) and, when he learns of the object of his mission, volunteers to join them. The group also meets Bundle, a comic relief bumpkin played by Bandal, who ends up joining the safari as a porter.

It is not long after the safari sets out that they are attacked by a tribe of pygmies. Tarzan, who has presumably been following them all along, takes advantage of the chaos and kidnaps Leela. We then follow the arduous journey that Tarzan, Leela slung over his shoulder, must make to get her back to his cave. In this he is accompanied by Dog Mothi, now full-grown, and Dada. And it is here that we reach the sober realization that Dada, one of the most egregious racial caricatures that I’ve seen in any of these films, is meant to be a replacement for Cheetah, who does not appear in the film at all.

Once encamped, Tarzan and Leela start the intermittently playful roughhousing that I think is meant to show that Leela is a sturdy, rambunctious girl worthy of Tarzan’s affections. Anyway, it’s included in every film that endeavors to present Tarzan’s origins, and varies in violence according to how much each film wants to traffic in the rape fantasy aspects of the story. In every case, it ultimately leads to the two falling in love, which may be the Tarzan series’ most odious contribution to the world of fiction.

The next section of the film feels obligatory but cozy, as Tarzan alternately woos Leela and rescues her from hungry tigers and crocodiles. Finally, when Tarzan isn’t looking, Leela wanders off and is captured by a tribe of cannibals who, in a tantalizing shout-out to another classic Hollywood film of the era, worship a statue of a giant ape. Once confined to the dungeon, Leela finds that her father and his party, including little Mothi, have also been captured. With all of their encouragement, Mothi breaks free and goes to fetch Tarzan, who hastily returns to kick cannibal ass.

And it is here, in the film’s final half hour, that director Homi Wadia—who, with his older brother JBH Wadia, practically created the stunt genre in Indian cinema, really displays his acumen for action. Toofani Tarzan’s finale is a nonstop gauntlet of narrow escapes, perilous stunts, pitched battles involving dozens—if not hundred--of extras and gruesome jungle justice, all of it expertly shot and choreographed. And while you’re watching it, you can’t help being struck by the fact that, whether you knew it or not, this is what you were waiting for.

And, of course, when the smoke clears, the true villain of the piece is revealed; Beharilal, who has all along been plotting to steal the formula for the immortality drug from around Tarzan’s neck—and I’ve already told you what happens to him.

Put simply: Toofani Tarzan is a solidly entertaining film, one that is of historical importance for being the one film, more than any other, that kicked off the Tarzan craze in India. Given that, it is surprising that, in its wake, no other Tarzan film would be made in India for twenty years. Meanwhile, back in the States, RKO and Johnny Weismuller shepherded the Franchise into the forties with several more films. Among these was 1942’s Tarzan’s Triumph, in which Tarzan contributed to the war effort by killing a bunch of Nazis who had somehow found their way into the Jungle.

The first trope is the fantasy of white mastery that Hollywood has perpetuated throughout its history, most recently in nonsense like Dances with Wolves, The Last Samurai and Avatar. The idea that a white man could not only adapt to an indigenous culture, but master it to the extent of earning the reverence of its people, is risible enough, but when that white man is a simpering buffoon, it’s downright hysterical. As much as Hollywood has tried to save Tarzan’s reputation with prestige pictures like The Legend of Greystoke and family oriented animated fare like Disney’s Tarzan, Tarzan still stands out as one of American culture’s most naked examples of the White Savior, and deserves to be called out for all the condescension and impotent power tripping that implies.

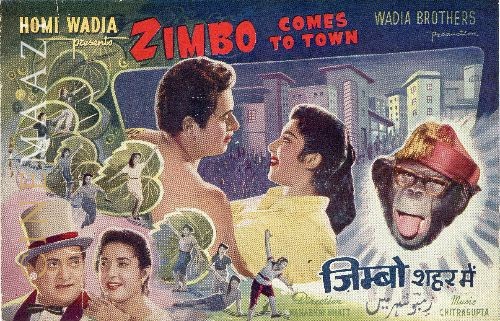

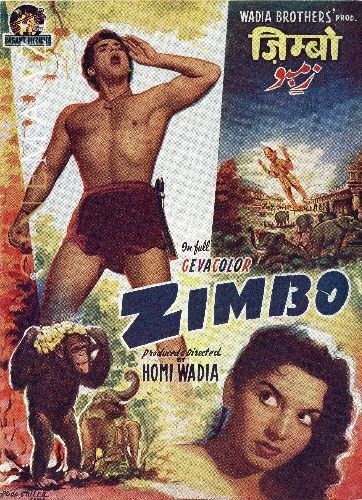

Zimbo stars the actor Azaad (full name Azaad Irani) in its titular role, and, while it probably could have gotten over with a lesser actor, it benefits immeasurably from his presence. While meeting all the role’s physical requirements, Azaad at the same time displays a gift for self-effacing, rubber-faced comedy, as well as a shrewd understanding of the film’s overall sense of camp.

Zimbo, too went on to receive popular acclaim, spawning two sequels, Zimbo Finds a Son and Zimbo Comes to Town. That its impact was worldwide is evidenced by, among other things, the 1974 Italian film Zambo, King of the Jungle and his appearance in an Israeli pulp magazine where he meets Tarzan himself (more about that later). I think the key to the films’ success is that, despite their outrageous campiness, they were also obligated by their genre to be thrilling and action-packed. Thus, alongside Zimbo doing an effeminate dance to “Limbo Rock”, we also got to see him deliver savage justice to a series of giant stuffed tigers and rubber alligators. By this, they achieved the Bollywood mandate of providing a little of something for everybody.

.jpg)

The Filipinos, always happy to take a good-natured pot shot at a beloved Western archetype, roasted Tarzan in two different film series. The first was a pair of films starring the revered film comedian Dolphy; Tansan the Mighty (sic) from 1962 and Tansan vs. Tarsan from 1963. The second series, shot in the late eighties and early nineties, was a trio of films starring comedian Joey De Leon; Starzan: Shouting Star of the Jungle, Starzan II, and Starzan III.

Finally, the Mexican film Tin Tan, El Hombre Mono from 1963, like most Mexican comedies of its era, is good natured, broad and modish. It stars Mexican comedian German “Tin Tan” Valdez as a mustached Tarzan and, like the Zimbo films, capitalizes on the comedic possibilities of Tarzan being pure sexual chocolate for any woman that gazes upon him. At times it’s comes across like as a cross between Betty and Veronica and The Flintstones as the buxom, leopard-print-clad starlets Ana Berthe Lepe and Ingrid Garbo fight over Tarzan with cartoonish giant clubs. Its high points are a crude special effect shot of Tin Tan inside the stomach of an alligator and the Technicolor go-go party sequence that closes the film. It plays out like an over-long burlesque show sketch, but is kind of enjoyably dopey if you’re in the right mood.

When Azaad was not available to play Tarzan, one of the actors who was available to step in was professional wrestler and reigning stunt film king Dara Singh, who had already played mythological strong men Hercules and Samson with pillar-rattling gravitas. While perhaps no great thespian, Singh had the physical presence and cheerful charisma necessary to pull in an audience, as well as an avid following from his days in the ring.

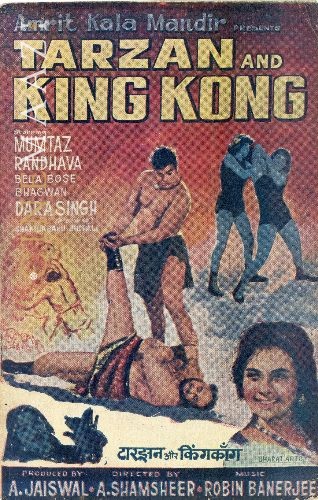

One of the high points of Dara Singh’s career as Tarzan is the aforementioned Tarzan Comes to Delhi, which was likely inspired by the Johnny Weismuller Tarzan movie Tarzan’s New York Adventure. The other is the misleadingly titled Tarzan and King Kong, in which he starred but did not play Tarzan. That honor went to his little brother Randhawa, a budding stunt film king in his own right.

Tarzan and King Kong generated a lot of internet speculation before it turned up on VCD in the early aughts and the cruel bait-and-switch of its title was revealed—that being that the King Kong of the title, rather than Willis O’Brien’s legendary giant ape, was instead an obese Hungarian wrestler with unruly mattes of hair all over his body. It’s true that this King Kong was Dara Singh’s arch enemy in the ring, and that his billing here is appropriate, but how were American fan boys who’d become obsessed with what the tantalizingly named film might contain to know that? As if in precognition of that fact, Tarzan and King Kong tosses in a climactic scene in which a man in an ape costume walks off with the heroine, only to be stabbed to death by Tarzan. Luckily, the film has generated enough good will by that point to earn a pass from more forgiving viewers.

The film begins with plane crash survivor Sharmila (teenage starlet Mumtaz) waking up to find herself floating on a piece of wreckage in a lake surrounded by dense jungle. Tarzan rescues her and, though he is once again portrayed as a great grunting dumbass, she can’t help being instantly smitten with him. Sharmila is a modern girl through and through, and wastes no time in teaching Tarzan to do the Twist. Unfortunately, their frolics are witnessed by Princess Shibani, who is absolutely gaga over the Ape Man. Furious, she resolves to both seduce Tarzan and get Sharmila out of the way by any means necessary. Unfortunately, her chosen means of seduction is to serially capture and imprison Tarzan, which doesn’t quite have the desired effect.

Bela Bose, a regular player in stunt films who also performed “item girl” roles in mainstream Bollywood films, brings a lot to Tarzan and King Kong. Her Shibani is obsessed with Tarzan to the point of being literally heart sick. She is so driven to distraction by him that she neglects her kingdom, letting it descend into decadence (as represented by a girl-on-girl wrestling match that is one of the film’s campy highlights.) All in all, Bose succeeds admirably in making sympathetic a character who in other films would be treated as a misogynistic caricature. This among other attributes makes Tarzan and King Kong one of the films covered in this article that I would heartily recommend.

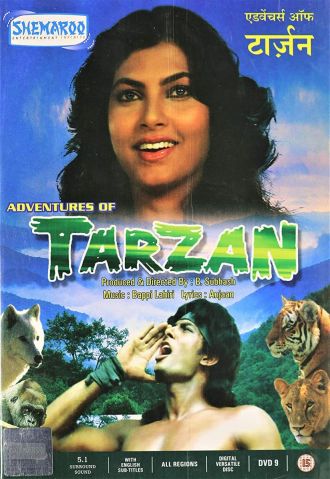

Finally, in 1985, Indian director Babar Subhash, who had turned young star Mithun Chakraborty into a superstar with his garish disco musical Disco Dancer, decided to make the Indian Tarzan movie to end all Indian Tarzan movies. Adventures of Tarzan was shot in India for a budget of 30 million INS and stars newcomer Hemant Birje as Tarzan, Kimi Katkar as Ruby/Jane, and famed character actor Om Shivpuri as Ruby’s dad, Shetty.

Almost as soon as these explorers arrive in the jungle, they are attacked by a tribe of paunchy natives in briefs and driven into the forest. Ruby almost immediately falls into a river in her diaphanous dress, as she is won’t to do. This affords beast and audience alike a healthy gander at her magnificent breasts, but also has the unfortunate effect of garnering the rapey attentions of some nearby savages. This gives Tarzan his first opportunity to rescue Ruby and the spoiled Ruby her first chance to come to the understanding that Tarzan is a real human being with feelings rather than the savage animal her dad has led her to believe.

Like the second Toofani Tarzan, Adventures of Tarzan earns its welcome with an absolutely stunning climax, a chaotic concatenation of explosions, rampaging animals, dangerous looking stunts performed on exotic looking circus equipment, and, in the case of the villainous DK, a well-deserved thrashing. Until then, it does not veer much from then standard template, other than to be just a little bolder in its presentation of sexual content (though not any bolder than the makers of Tarzan and his Mate some fifty years previous.) It’s a perfectly entertaining film, with just enough of a trashy edge to lend its more questionable content a prurient thrill. It also distinguishes itself by overcoming a typically lazy Bappi Lahiri score—the songs from which variously lift their melodies from “Do Re Mi”, “Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep” and “Georgy Girl.” Whoever did the incidental music compensates for this shortfall by contributing some native chants that are both catchy and percussive.

Jungle Ka Sher starts in grand C movie tradition, with eight solid minutes of Tarzan (Amit Pachori, here referred to as “The Jungle Lion”) completely wilding out; throwing people left and right while yelling and scowling menacingly. He does this until he sees Ruby/Jane (Sapna Sappu) bathing in a nearby lake, at which point he freezes and twinkly music box music starts to play on the soundtrack.

Like many low budget Indian action movies Jungle Ka Sher plots itself out as follows: A square area of public space is delineated--in this case what is likely a public park with both a paved road and well-defined paths—and an assortment of oddball characters is placed within it to wander about and randomly encounter one another. And when they encounter one another, they either kill, screw, beat, or scream and point at each other. This constitutes the action of the movie. The oddball characters this time around are Ruby’s father, John, who is an evil poacher, a skinny septuagenarian fellow who keeps referring to himself as “Gorilla” and commands a lackluster band of natives, and Nagina, a sexy snake lady. All of these people at one time or in concert want to see Tarzan/The Jungle Lion dead.

One of my favorite parts of Jungle Ka Sher is how the character of Ruby is introduced. Here she comes, happily driving down the jungle’s one paved road in her jeep, only to unaccountably drive straight off the road and into a tree, even though she was going at a moderate speed and there was no other traffic in sight. Then, of course, she falls in a river.

Tarzan’s resulting ubiquity in Indian cinema is a testament to genre film’s element of ritual. When Tarzan is presented on screen, it is as a talisman that instills in us a kind of anticipatory thrill. And that anticipation is rewarded with the first appearance of Jane, the first white interloper, the first manifestly fake stuffed tiger, the first rubber alligator and, of course, the climactic stampede. Once these have transpired, we feel cleansed, purified—and perhaps inspired to bring a little more heroism to the mundane tribulations of our daily lives; the dreary day job, the routinized marriage, the stultifying gauntlet of modern humanity. These we will no longer greet with a bowed head and furrowed brow, but with a raised head and a rousing cry in our lungs.

Tags

About the Author

Todd Stadtman is a musician, author, DJ, podcaster and blogger whose first book, Funky Bollywood: The Wild World of 1970s Indian Action Cinema, was published by Britain’s FAB press in 2015. He has also written a trio of mystery novels called The SF Punk Trio. For these, he relied heavily on his experience as a teenage punk musician in the early days of the San Francisco new wave scene. His work has also appeared in the publications Famous Monsters, The Times of India, and The World Directory of Cinema (Turkey Edition) and the websites Teleport City, i09, Mondo Macabro and The Cultural Gutter. He currently lives in Oakland, CA.

.jpg)