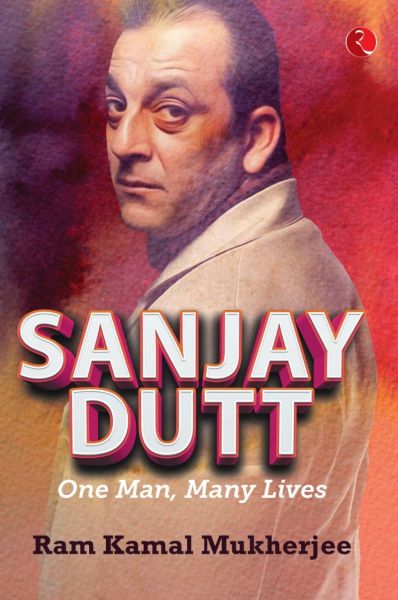

Sanjay Dutt: Between Myth and Reality

What the world knows about Sanjay Dutt is only half-truths.

Best-selling author, film producer and renowned journalist Ram Kamal Mukherjee unravels the enigma and stigma surrounding Sanju Baba.

There can be no last word on Sanjay Dutt. Ever. Even as he walks a free man after more than three decades of prison terms and controversies, Dutt remains a classic case study in all that defines the ‘star’ system in Bollywood—an industry known for its deep-rooted sense of entitlement. However, there is one question that dominates: Who is the real Sanjay Dutt?

Is he a man who has been ‘wronged by the media’, as his friend and filmmaker Rajkumar Hirani wants everyone to believe? Is he a son who could never recover from his mother’s death? Is he a son whose father’s political leanings made him an easy target? Or is he a myth, created by a consortium of film journalists, industry insiders, political fiends and adversaries?

Delving deep into both the man and his circumstances, Sanjay Dutt: One Man, Many Lives tells the uncut, untold and uncensored story of Sanjay Balraj Dutt. What emerges is an account—as much about one man’s laudable efforts to keep reinventing himself, as it is about his privileges. Privileges that were seldom earned and always taken for granted.

This is the closest anyone can ever come to understanding Sanju Baba.

The following are two excerpts from the book Sanjay Dutt: One Man, Many Lives.

After Rocky, Sanjay's drug addiction had peaked. One day, he woke up from a heroin binge and began to look for something to eat. The domestic help told him, 'Baba, you've slept for two days straight. Everyone in the house has gone mad with worry: Sanjay looked at his face in the mirror, went to his father's room and said, `Dad, I am dying. You have to save me: He was first taken to the Breach Candy Hospital Detox Center and then to a rehab centre in Texas. Sunil Dutt, being the conscientious person that he was, informed all the producers that his son was an addict and that until and unless he cleaned up his act he was not coming back.

Dutt was sent to the same place that had treated his mother: Sloan and Kettering. The road to recovery was a slow and painful one. And it lasted for over eight months.

When he was asked if he started doing drugs again because his mother, Nargis, passed away, Dutt said, in an interview to The Times of India, 'Its not that I started because of mom. Mera dog mar gaya toh daaru pi raha boon, aaj mera gadha mar gaya to daaru piyunga (I am drinking because my dog has died, I will drink because my donkey died today)—these are just excuses. Substance abuse is something that you do if you want to do it. Once you get into it, it's very difficult to leave. It is the worst thing in the world. My journey with substance abuse lasted for about twelve years. There are no drugs in the world that I have not done. When my father took me to America (to the rehab centre), they gave me a list (of drugs) and I ticked every drug on it—because I had taken all of them. The doctor told my dad, "What kind of food do you eat in India? Going by the drugs he did, he should be dead by now!"'

Dutt confessed he did not quit drugs because of his family. 'I left because I wanted to be out of it. I didn't want that life. When you start the rehabilitation process, one part is physical—your body breaks down and you feel cold. But the most difficult part comes later, when your mind says, "Ab toh tu theek ho gaya hai, ek baar maar lete hain (now you're fixed, let's just do it one more time):' That's when you have to use willpower.' Since he got clean, and was cleared of all charges in the long-drawn legal cases, he has been a regular at anti-drug panel discussions, where he tells youngsters, `Live your life, love your work, love your family. It is better than cocaine:

Sanjay Dutt may not have spoken the truth on every occasion. He may have hidden some facts. But when it comes to his addiction, even his fiercest critics will tell you that he is brutally honest.

Post rehab, Dutt was a lot more at peace with himself. Reports began emerging in film magazines that he had struck up a friendship with a cattle rancher named Bill. He had invested in a long horn cattle ranch of his own; he was in the midst of nature, building a new life for himself. He had bought a small flat in New York and was planning to run a steakhouse in the city. However, two months later, Sunil Dutt flew down to meet him. He wanted his son to come back. Sanjay didn't want to return; he didn't want to do films. But his father pleaded, and eventually, despite all the years of resentment, misunderstanding, angst and hurt, Sanjay gave in.

Back in India, everyone had written off the prodigal son—the charsi, the addict, who had brought shame to the Dutt family. But in the first of many 'comebacks' that were to follow, the fresh-from-the-American-farm Sanjay devoted his energy to sculpting his body and starred in Naam, one of the biggest hits of 1986.

A reporter working with some of the leading city newspapers, Anand Holla, offered a ringside view of the court's proceedings, which he said marked a 'crucial moment in India's judicial history: In a piece written for Arre (global), Holla recalled that day in 2007 when Dutt's life hung in the balance once again. Those were the heady days post-Munna Bhai. And the success of the films had stirred fan loyalties. But the wave of affection and sympathy stopped short of the walls of the TADA court. Describing Dutt's demeanour during the court hearings, Holla wrote,

In a quiet corner by the discoloured metal stairs that swirled upward, Dutt, dapper in his staple attire of a full-sleeved blue shirt with three buttons undone, denims, tapering boots, a fistful of gold chains, and hand-swept hair, grew mildly animated upon my mention of his blockbuster. 'You know, kids love Circuit way more than they love Munna Bhai. I have a live example in my family,' he said, chuckling, his head tilted to the side. [ ... ]

`It is strange,' he continued. 'I am obviously happy about Lage Raho's success, but I also have no idea what the judgment will be. It's a different world here ...'

A few weeks after this exchange, Judge Pramod Kode handed out an emphatic clean chit straight out of a simplistic movie sequence—`You are not a terrorist'—and a cascade of sweet relief swept over Dutt's sweat-speckled face.

According to those who had followed the star, including Holla, he was rather unremarkable inside the court—'unpretentious' and displaying a certain 'naiveté, sometimes even to the point of not caring. He would sometimes regale the accompanying journalists with trivia from his life on the set, where he belonged. Holla recalls how he once told him: 'Dancing is tough for me ... when David (Dhawan) asked me to do these ridiculous dances abroad, like in Europe, it got so embarrassing, I'd tell David, "Ab bas bhi karo, Sir (Let's stop now, sir)!"'

There was more. Sometimes Dutt would saunter in, droopy shoulders, robotic stride. `...unmistakably inebriated, his heaving breath betraying whiskey. He'd empty sachets of Manikchand gutkha, and if you caught his eye, he'd just wink at you and chomp away,' wrote Holla.

All reporters covering the trial agree that despite the seemingly vice-like grip of the legal cases, Dutt always got away with way too many exemptions from appearances. His busy shoot schedules and his lawyer were always handy. Even during his incarceration between 1993 and 1995, when there were stories about the hardships he faced in prison, Holla says he had his way around certain things. Apparently, 'a special coconut oil was called for, to nourish his long mane; regular coconut water in polythene pouches to soothe his damaged kidneys. The fact that he would pour the latter in a steel glass and take endless little sips from it while munching on packaged snacks convinced at least some reporters that the coconut water was mixed with something more robust ... like vodka. Just like the old stories about Dutt drinking the blood of a freshly slaughtered reptile just for a dare, this, too, hovered between myth and reality. Like everything else in his life.

There was a time when Sunil Dutt, who had fought like a lion to keep his son out of jail, had to come to terms with the fact that he had failed. His political party, the Congress, failed him. There were whispers about how the party heavyweights had kept him waiting for hours and refused to grant him an audience. And that his public empathy for the minorities was something that the present disposition was not comfortable with. It was a huge blow to the parliamentarian, who had spent a lifetime serving his people and his party.

Then, one day, Sunil Dutt visited his son in prison, and broke down. 'I am sorry, son. I cannot help you anymore.'

This has been reproduced from the book Sanjay Dutt: One Man, Many Lives written by Ram Kamal Mukherjee.

The banner image did not appear with the original publication and may not be reproduced without permission.

Tags

About the Author

Ram Kamal Mukherjee, India’s first Power Brand film journalist, is a columnist, producer and director. Winner of many coveted titles, Ram Kamal is one of the most popular personalities and influencers in the Indian film fraternity. He has worked as Editor-in-Chief of Stardust, India’s leading film magazine. A film journalist for twenty years, he was also associated with The Times of India, The Asian Age, Mid-day and

Anandabazar Patrika. As Vice President of Pritish Nandy Communications, he has worked on twelve feature films. His biography of Hema Malini, Beyond the Dream Girl (2017), won him five prestigious Best Author awards. Ram Kamal has written a coffee table book, Diva Unveiled (2005); a work of fiction, Long Island Iced Tea (2016); and a collection of Hindi poems, Muktakash (2019).

Ram Kamal launched his own production house, Assorted Motion Pictures, with his critically acclaimed directorial debut Cakewalk. He has also completed a second short feature film, A Tribute to Rituparno Ghosh: Season’s Greetings.

.jpg)